Birth of the Flight Simulator: Genius and Scandal

The story of the first flight simulator is one of innovation, political scandal, and death.

This column is the first in a two-part series about the Link Trainer, the world’s first flight simulator.

Edwin Link had a passion for flying. He took his first flight in 1920 at the age of 16, and by 1927 he was a convert, borrowing money from his parents to buy a Cessna Model AA. He planned to make a living barnstorming, training, and flying charter flights, but money kept him grounded. Being a private pilot meant constant fuel and maintenance expenditures, and flight instructors were tough to find in Link’s hometown of Binghampton, New York. But Link was a tinkerer and problem-solver by nature, and he had one major advantage in his corner — the family organ factory.

The Link Piano and Organ Company mainly built player pianos for silent movie theaters, but it also sold pipe organs and some early jukeboxes. The family business was on rocky ground, but it gave Link exactly what he needed — a workshop and a limitless supply of spare parts. There, in the factory basement, he would build the world’s first flight simulator — a machine that would save lives, fight wars, and help get men to the moon.

But Link had an uphill fight ahead of him. The Link Trainer had to battle skepticism, the Depression, and outdated ideas on its way to popular adoption. In the end, it took a slew of deaths, and a looming military scandal, for the Army to see value in simulating flight rather than learning on the job.

It took Edwin Link 18 months to create the “Pilot Maker,” a working prototype of what he’d eventually dub the “Link Trainer.” It didn’t look like much from the outside — it resembled a child’s wooden plane, complete with stubby wings and a tail — but the inside had a replica of a single-seat cockpit, complete with stick, pedals, and instruments.

And all of it worked. The little wooden plane sat on a universal joint, with a set of electrically-powered pneumatic bellows able to tilt it this way and that. Pull the stick back and the nose would rise into a climb. Push the foot pedals and it would tilt as if banking. Link’s device could simulate pitch, yaw, and limited roll, responding much the way a real aircraft would. Soon, Link was using the apparatus to fill in the gaps of his training. By the early 1930s, Link and his brother were operating an after-hours flight school at the factory, charging students $85 for flying lessons in the Trainer.

Link, always the tinkerer, continued improving his device. Quiet and creative, his mild exterior masked an active mind. Link’s brain pumped out inventions — from early jukeboxes to piano mechanisms — often so fast that they overlapped each other. He could barely finish one before rushing off to another, yet the Trainer would prove an ongoing love affair.

By 1930, rival pilot trainers were starting to emerge, and Link rushed to patent an improved version of the device. This new version was much like the first, but used a mixed system of vacuum and pneumatic bellows that made the device less jerky. This also allowed Link to feed the pneumatic system into the instrument panel, making some of the gauges functional and allowing students to conduct instrument training — in other words, to fly the plane without visual reference.

Critically, the Trainer did lack a windshield. With the top hatch down, the pilot sat enclosed with the instruments, unable to get a visual reference. This not only made the plane’s movement feel more real, it also forced the trainee to fly by nothing but instruments—a method called “blind flying” that wasn’t common in the early 1930s. This was an era, one must remember, where civil aviation was in its infancy. The first purpose-built passenger airliner wouldn’t launch until 1935, and civilian aviation was the territory of amateur enthusiasts and a plethora of small airlines that survived off government air mail contracts. Common wisdom held that a student would learn to fly airplanes by flying airplanes, an outlook that emerged from the military’s WWI training ethos.

So when Link demonstrated the system for the US Army Air Corps in 1931, he didn’t receive a warm reception. Opinion was stacked against him from the start. Army old guard felt an over-reliance on flight instruments produced weak pilots, and with the Depression shrinking military budgets, a new system seemed a costly extravagance. What’s the sense of approximating flight on the ground, they reasoned, when you can give pilots real-world experience in the air? After all, pilots largely flew on visual reference and navigated by radio — what would the use of this closed-in system be? Top brass believed there was no point training for bad weather because the Air Corps didn’t fly in bad weather.

In hindsight, the military should’ve bought the Link Trainer on sight — if they had, it might’ve saved a dozen lives and mitigated a political scandal that rocked the FDR administration.

Neither Snow, Nor Rain, Nor Gloom of Night…

In 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt swept into office on a wave of public support, promising an activist administration that would reform the government and punish abuses that led to the Great Depression.

In 1934, Roosevelt targeted the country’s air mail system. While American air mail was the envy of the world, it was also prone to abuse by commercial airlines that flew loads on behalf of the Postal Service. When a congressional probe uncovered evidence suggesting the airlines had engaged in price fixing, Roosevelt saw his opening. The president immediately cancelled all government air mail contracts and suggested the Army Air Corps take over.

The same day, the Postmaster General’s office called a meeting with Maj. Gen. Benjamin Foulois, Chief of the Army Air Corps, and asked him if the Corps could operate the country’s air mail service. Foulois — without consulting anyone, even his deputy — answered that the Corps could begin mail flights in a week to ten days.

Exactly why Foulois was so gung-ho about air mail is still a matter of debate. The military’s can-do ethos certainly played a role, but political factors were also in the mix. Government austerity during the Depression meant fierce budget competition, and the Air Corps — which was less than a decade old — needed a public win to demonstrate it was both capable and necessary. And in the end, no one likes to say no to the president.

The problem was, the Air Corps wasn’t equipped or trained to fly mail routes. Depression-era budget restrictions limited the number of flight hours during training, and Air Corps planes, instruments, and radios weren’t as new as the commercial operations they were expected to replace. Most of the aircraft assigned to the task were converted fighters or bombers, not cargo planes. Many lacked two-way radios, meaning pilots could receive transmissions but not broadcast them. Fully a third of the planes were open cockpit — terrible equipment for a winter-time operation that expected planes to fly over mountain ranges.

But perhaps the most dangerous element was the lack of instruments. Though the Army Air Corps owned instruments that would help with navigation and “blind flying,” they sat unused in a warehouse — earmarked for newer aircraft than those in the Air Mail Operation (“AMO”). Regardless, the pilots wouldn’t have had time to train on them, since the Air Corps was a fair-weather air force that, due to fuel prices, didn’t operate at night or during bad weather.

It was exactly the problem the Link Trainer was designed to solve.

As mechanics scrambled to modify the AMO’s equipment, installing new radios and updating instrument panels, Maj. Gen. Foulois told a House committee that the Corps had “a great deal of experience in flying at night, and in flying in fogs and bad weather, in blind flying, and in flying under all other conditions.” Though they didn’t know the routes, he insisted, they would keep the schedules.

Days later, the deaths began.

Meanwhile, At the Fairground…

As the Army prepared to send half-trained pilots into the air, Edwin Link had found a new customer for his trainer: amusement parks.

Though he’d designed it as a training aid, Link understood that simulations could also let people live out fantasies. In the absence of government contracts or flight school orders, he added a coin slot and marketed the device as an interactive ride. While fun was never Link’s primary goal — to him, the device was a training aid — he foresaw the potential of simulation as entertainment. Clearly, not everyone wanted to fly planes, but plenty of people would drop a quarter ($4 in today’s money) to feel like they were flying a plane. It was an innovation that, to a certain extent, foreshadowed modern gaming.

Despite this success, the Depression hit Link hard. Few had the disposable income for flight lessons, and schools didn’t want to dump money on a new trainer. His parents’ organ factory closed in 1932. Ever creative, Link developed an electric under-wing advertising sign for his Cessna, and made extra money as an ad flyer and working as ground crew at local airports. The experience meant flying at night and in bad weather, with each bump and fog bank giving Link more data to build into his always-improving device.

Though it didn’t make much money, the Trainer brought Link some publicity, as well as an unexpected partnership. In 1929, a local newspaper dispatched Marion Clayton — a cub reporter fresh from Syracuse University — to interview the quiet man about his wooden plane. The two married in 1931.

“I married my best story,” she liked to joke, and that was true in more ways than one. Marion Link would manage the business side of Link Aviation, Inc.

But even with Edwin tinkering and Marion handling the books, Link’s company was by no means secure in February of 1934 — when Air Corps pilots began to crash.

“Legalized Murder”

The Air Corps lost its first three pilots on February 16th, three days before mail flights officially began. That morning, two lieutenants on a training run from Salt Lake to Cheyenne crashed into a canyon wall after hitting high winds and snow. Later that day, an inexperienced pilot took off from the same airfield, got lost in fog, and died trying to make an emergency landing in Idaho.

Eddie Rickenbacker, a celebrity WWI ace — and a paid consultant for the spurned commercial airlines — called the operation “legalized murder.” To add insult to injury, the airlines staged a cross-country flight — a publicity stunt to show how capable they were. The press ate it up, sensing scandal.

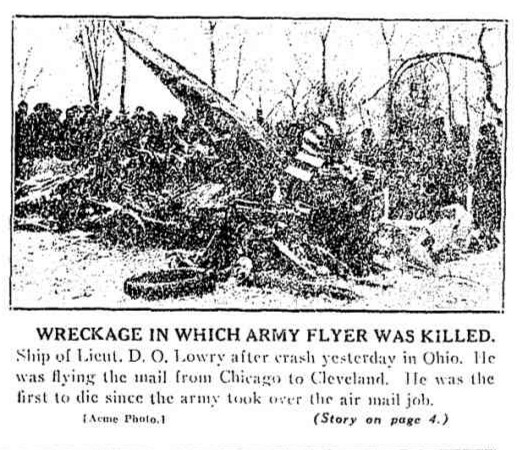

The crashes continued without mercy. Three planes went down on February 22nd, killing two pilots. In the most horrific incident, Lt. Durward O. Lowry took off from Chicago and got disoriented when he hit a snowstorm. Fifty miles off course, with a malfunctioning navigational radio and a near-empty fuel tank, he bailed out — then died when his parachute caught on the plane’s tail housing.

Lowry’s mother learned of her son’s death while riding the bus in Detroit. She saw the headline on another passenger’s paper.

“They shouldn’t have had to fly at night through winter storms,” she told the Chicago Tribune. “Over unfamiliar courses that it took months for commercial pilots to learn.”

The Air Corps lost six pilots that week.

Newspapers filled their pages with crash news, peppering their columns with descriptions of planes flipped over or dashed to pieces, scattering mail like confetti on fields and woods. The violence was more shocking because it was close the home. These boys weren’t dying over battlefields overseas, they were slamming into fields in Texas and drowning off Rockaway Beach.

It was a bad year for air crashes in general. The winter of 1934 was a harsh one, and deaths — both civilian and military — spiked. But this was more than that. These were barely-trained pilots flying outdated planes, with unfamiliar instruments, in bad weather. The upgrades caused problems too — Army mechanics installed new instruments incorrectly, and couldn’t standardize instrumentation layout, meaning pilots got confused during a crisis. Crew took to going up with flashlights, lest their cockpit lighting wink out and plunge them into darkness. Air Corps officers criticized the operation in public, fueling the press frenzy. Republicans smelled blood, sensing their first leverage against an administration was widely popular due to the New Deal and repeal of Prohibition. Critics called for an investigation.

On March 10th, Roosevelt halted the operation and called General Foulois — and Army Chief of Staff Douglas McArthur — to account for the accident record. By that time, the three-week operation had seen 31 major accidents and ten fatalities. The embattled Roosevelt asked Foulois when the killing would stop.

“Only when the airplanes stop flying,” Foulois answered. Roosevelt was furious.

Air Corps mail flights resumed, and continued until June 1st of that year. Foulois stemmed the casualties by barring inexperienced pilots from bad-weather flights, and acquiring new planes and instruments. Crucially, the weather improved. But the operation was already a fiasco — 66 major accidents with 13 crew deaths. A congressional investigation forced Foulois to resign, and insisted the Air Corps review its training and modernize equipment.

With the weight of thirteen dead crewmen on it shoulders, the Army called Edwin Link.

Link Breaks Through

A few days later, a huddle of Army officers waited at Newark Airfield, convinced that they were wasting their time.

New Jersey was socked in with fog — pea soup fog — the kind that had claimed so many pilots and aircraft that year. Link had promised to fly in from Binghampton, but it was clear he wouldn’t make it.

The officers were getting ready to leave when they heard the buzz of a Cessna engine. Link’s plane descended out of the fog and touched down — the exact sort of low-visibility landing that had killed so many airmen during the AMO.

It was the best demonstration Link could’ve made.

The Army ordered six Link Trainers at $3,500 per unit. They would eventually order 10,000 more.

But that was only the beginning — soon, Edwin Link would receive telegrams from London, Tokyo, Berlin and Moscow — and the quiet inventor from Binghampton would be in a political game much bigger, and more dangerous, than an air mail scandal.

Next Week: The Link Trainer instructs 500,000 pilots — both Allied and Axis — and helps carry mankind to the moon.

Pictures from The Canadian Museum of Flight, Wikimedia Commons (by Bzuk [own work]), and Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

Robert Rath is a freelance writer, novelist, and researcher based in Hong Kong. His articles have appeared in Zam, Vice, The Escapist, Playboy and Slate. You can follow his exploits at RobWritesPulp.com or on Twitter at @RobWritesPulp.